- Home

- Lisa Jahn-Clough

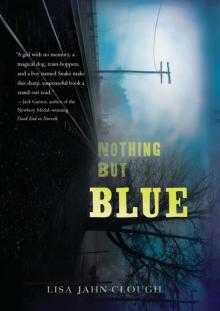

Nothing But Blue

Nothing But Blue Read online

Table of Contents

Title Page

Table of Contents

Copyright

Dedication

Now

Before

Now

Before

Now

Before

Now

Before

Now

Before

Now

Before

Now

Before

Now

Before

Now

Before

Now

Before

Now

Now and Before

Acknowlegements

Sample Chapter from COUNTRY GIRL, CITY GIRL

Buy the Book

About the Author

Copyright © 2013 by Lisa Jahn-Clough

All rights reserved. For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

Houghton Mifflin is an imprint of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company.

www.hmhbooks.com

The Library of Congress has cataloged the print edition as follows:

Jahn-Clough, Lisa.

Nothing but Blue / by Lisa Jahn-Clough.

p. cm.

Summary: Aided by a mysterious, possibly magical dog named Shadow and by various strangers, a seventeen-year-old with acute memory loss who calls herself Blue makes a 500-mile trek to her childhood home, unaware of what she has left behind.

ISBN 978-0-618-95961-7

[1. Amnesia—Fiction. 2. Voyages and travels—Fiction. 3. Dogs—Fiction. 4. Human-animal relationships—Fiction. 5. Homeless persons—Fiction. 6. Death—Fiction. 7. Moving, Household—Fiction.] I. Title.

PZ7.J153536Not 2013

[Fic]—dc23

2012026971

eISBN 978-0-544-03566-9

v1.0513

Know the universe itself as a road,

as many roads, as roads for traveling souls.

—Walt Whitman

NOW

All dead. No one survived. All dead.

The words pound in my head like mini explosions going off again and again and again.

All dead. Boom!

No one survived. Boom!

All dead. Boom!

I don’t know what these words mean. I am not dead. I am here, so I have survived. The heavy fog dampens my clothes so that my cutoffs cling to my thighs. I touch the air gingerly, then grab at it as though I can hold on. I rub my fingertips together. They are wet and clammy from the humidity. I feel, therefore I must exist.

I’m not sure where I am. I’ve been walking since morning, so I must be miles from wherever I began. It’s afternoon now.

I find a plot of grass and a tree to lean against. The bark is rough and hard on my back, but it’s solid. I flip off my flip-flops and massage one foot, then the other.

I check my pockets. Maybe there’s something useful tucked away. I take out a door key on a mini-flashlight key chain. I blink the beam once, twice, three times and swirl the white light. I can barely see the glow in the misty air.

In the other pocket is a roll of Life Savers. I am suddenly aware that I have not eaten all day. I pop one into my mouth, then two more. I am about to take another when I think perhaps I should save the rest. I fold over the foil wrapper and seal it down with my thumb.

I turn the Life Savers around with my tongue and suck out the sweet juicy flavor to make them last longer. I long for a candy bar, something with hard, dark chocolate outside and gooey, chewy, sweet caramel inside.

The sky darkens under a cloud and the wind blows. It looks like it’s going to rain, maybe storm. The days are getting shorter. School will start soon. It will be my last year of high school, but I don’t think I’ll be going now. I can’t shake the feeling that something absolutely awful has happened.

One fat droplet splats on the top of my head. Expecting a downpour, I pull up the hood of my sweatshirt, but there is only that one drop. I’m glad to have the sweatshirt though. I think hard. I try to remember. I almost didn’t take it with me. I grabbed it off the chair on my way out the door. It was early in the morning. Was that this morning? What was it I had to get? A cup of coffee? I never got it. I forgot the money. I was going back to get some, and that’s it.

Now I don’t have the coffee and I don’t have the money and I don’t know what happened.

Boom! Boom! Boom! throbs my brain with the struggle to remember. I beat my palms on my forehead. The exploding will stop if I can just stop thinking.

I search deeper in my pockets. Maybe there’s some cash. I do that sometimes, fold up a bill and stick it in my pocket, then forget about it until I next wear the pants and find it all washed and crumpled. I turn the front pockets inside out. Not even a coin—nothing but lint.

So this is what I have:

• half a roll of Life Savers

• one front-door key (useless)

• one flashlight key chain

That’s it. That’s all she wrote. No more. No less. Once I had everything, and now, nada. No money, no phone, no music, no food, no clothes—well, except for the clothes on my back: sweatshirt, T-shirt, cutoffs, flip-flops, underwear. Hard to believe I could be so stupid as to take so little, but I was only going for a few minutes, or so I thought.

I hear my mother’s voice somewhere in my head: You’re going out in that?

And my father: You really should wear better shoes.

Mother: You just don’t have the legs for such short shorts, dear.

Father: I don’t see how you can walk in those. There’s no support.

Mother: At least brush your hair.

Father: We just want what’s good for you.

Mother: We just want you to be a normal, happy, pretty girl …

Did they actually say these things, or am I imagining things they might say? They always said they just wanted me to be happy. Do they even know I’m gone?

Where are they?

Where am I?

All dead. No one survived. All dead.

My throat tightens and my stomach twists into knots. It’s hard to breathe. I squeeze my eyes shut. There is a smell that makes me want to vomit. Burning. Smoke. Ash. I gasp for air.

I try to focus on the moment by counting breaths. One. Two. Three. Four. Five. Six. I inhale deeper with each count, and the chant grows quieter. By the time I get all the way to fifty it is so faint I can barely hear it. The stench disappears and my stomach loosens. I can swallow.

As I listen to my breath, I stare at an ant on the ground. It’s a tiny little thing carrying a crumb twice its size, trudging through grass and over dirt. Suddenly it runs into a twig, and instead of going around, it attempts to climb over without dropping its precious load. The poor little ant is all by itself in a world much larger than it will ever know. I move the twig out of its way, and the ant keeps going as though the twig had never even been there.

I make a pledge to myself—I won’t think of anything except what is in front of me. It is the only way. I have no future. I have no past. All I have is now—the clothes on my back, the raindrop on my head, the grass under my feet, the tree pressing against my spine, the woods on either side of me, and the long stretch of road ahead disappearing into a bank of gray fog.

I’m walking along the side of the road with my hood pulled over my face so no one can see me. The air is dark and heavy. My feet ache from the stupid flip-flops. I might as well be barefoot.

My stomach grumbles. I finished off the Life Savers hours ago. So much for saving. I imagine all the things I could eat: a bagel oozing out cream cheese, extra-cheesy pizza, stringy

mozzarella sticks, fried chicken fingers, a burger with loads of ketchup, french fries, potato chips, a mocha milk shake, a thick slice of chocolate cake for dessert. I lick my lips.

The rumbling of a pickup truck interrupts my food fantasy. I try to breathe normally even though inside I am trembling. My instincts tell me I shouldn’t be “found.” The truck comes up behind me. I stare straight ahead.

It will pass. It will not notice me. It will pass, I tell myself, like a mantra that will make it true. But it doesn’t work. The truck slows to my pace and drives alongside me. I keep walking. It will pass. It will pass.

The window rolls down and a guy calls out, “Want a lift?”

I don’t dare look, but I imagine a cliché truck guy: cigarette dangling from his mouth, the rest of the pack rolled in the sleeve of his T-shirt, a big grin revealing missing teeth, and some empty beer cans strewn about the front seat.

I shake my head ever so slightly, no, and keep walking straight ahead. My flip-flops slap at my heels with each step.

“You sure? It can be dangerous walking all alone. It’s gonna be dark soon,” the man says.

This is what every child is warned about. Never trust strange men who sound friendly. Especially men in trucks who offer rides. I make a mistake and glance at him. He is muscular and good-looking and wearing a T-shirt, but there’s no cigarette. He smiles wide, and as far as I can tell he has all his teeth.

He asks, “You from around here?”

Say nothing.

“Where are you headed?”

Keep walking.

He stops the truck. “Hey,” he says as he opens the door and steps out.

Everything in me panics. Now I know he is dangerous. He is planning to pick me up, leave me battered on the street, or worse. As he walks around the front of the truck I burst into a run, my shoes flopping and flailing. I have to get away from him. Fast. He yells something about calling for help, something about people looking for me, but I concentrate on running.

A sound echoes somewhere—a single, short bark, then another and another, like a beckoning call. It’s coming from the woods. Of course, stupid me. Why am I running straight down the road where he can easily catch me, when I should run where it’s harder to follow and easier to hide? I turn and head into the trees toward the barking.

The flower part of one of my flip-flops breaks, and the toe thong pulls out of the sole. I kick both shoes off and keep running. I ignore the sticks and twigs and rocks stinging my bare feet. I pray that the man has not followed me into the woods, but I don’t dare stop to find out.

I hear another bark and can make out the dark shadow of an animal in between the trees way ahead. It stands there for a second like it’s looking back at me, then takes off at a gallop and disappears into the depths of the forest.

***

I’ve been trudging slowly along and now it is quickly darkening into night. There’s not much along this road; it is straight and rural with a lot of cornfields. I stop at the next building I come to—a brick restaurant with a sign on the roof that reads FIREFLY in hot red letters. Under that is says: HOME-COOKED BREAKFAST AND LUNCH.

I am dying for something to eat and drink. Although dying may be an exaggeration. Funny how we use that expression so easily. Am I dying? Am I dead already?

All dead, all dead, all dead. No one survived. The words become a steady chant again, but this time I am better able to ignore them, since the grumbling of my stomach is even stronger.

I sit by the side of the building and cradle my tender feet. I’ve stubbed my toes more than once, and one of them is caked with blood. I spit on my finger and try to wash it off, but it smears a muddy, bloody streak across my foot.

A street lamp flickers and buzzes out. It is really dark now—there is no moon or stars. Tears burn in my eyes but I cannot cry. There’s nothing to cry about—this is just the way it is now.

Next to me are a couple of dumpsters. I bet there’s leftover food in there. I crawl over and peer inside the closest one. It’s all recycling—nothing but paper and cardboard. I go to the other. I shine the flashlight key chain into the foul depths.

The dumpster is full of black garbage bags, rotten food, Styrofoam containers, and other unidentifiable trash. The smell makes me want to puke. I snatch one of the containers and move away.

The container is half full of spaghetti soaked in red sauce with part of a meatball perched on the top. I poke the meatball with my finger. It’s mushy and totally gross. I can’t eat someone’s old leftover, thrown-out spaghetti dinner. This will make me sick for sure. Is it better to die of starvation or food poisoning? I place the box next to me. My stomach begs to be fed, but I’m not ready to eat garbage. Not yet.

I lie down on the hard, damp pavement. I close my eyes. I feel … nothing. I see … nothing. The chant is a buzz of white noise in the dark.

Then out of the blackness comes a vision of smoldering rubble, crumpled piles of wood, brick, rock—it looks like a war zone. The insanity of fire trucks, police, ambulance, neighbors screaming. That stench of smoke fills my nostrils again and dries my throat, as though the ash has crawled deep inside.

I hear words. This time they are not a chant but clear single words, one at a time: Explosion … Leak … Inside … Dead … Impossible … No, possible.

I see these images, I hear these words, but when I open my eyes all I see is the black pavement, the brick wall; everything else is just night. The street lamp hums and flickers on again, blazing the letters of the restaurant sign in red flashes. Firefly. Firefly. Moths hover around the sudden light and ding into it. The moon emerges from behind the clouds. A few stars blink. The nightmare images have nothing to do with me; my mind is playing tricks.

This is what is real: I’m freezing. I’m starving. I’m tired. I’m in pain. There is no way I can sleep like this. I need something to lie on and something to cover me.

Still shaking, I get up and go over to the recycle dumpster. I take out some of the larger boxes. I arrange them along the wall of the restaurant. I line the ground with the flat pieces, then make walls and a roof. I crawl inside and prop another piece against the opening, leaving a tiny crack.

It’s dark and musty, but I’m somewhat proud of my cave—like the pillow tents I made when I was little. No one could find me under a mound of pillows.

This time when I lie down it’s on a cardboard mat. At least it’s better than the pavement. I shut my eyes again and try to shut my mind at the same time. I breathe in through my mouth and out through my nose like they tell you in yoga. Or is it in the nose and out the mouth? I never can remember.

Breathe in. Count to ten. Breathe out. In. Count. Out. In. Count. Out.

Now all I smell is damp cardboard. All I hear are a few raindrops pittering on the roof. The rest drifts away. I am shut tight in this box, safe for the moment.

But not for long. Suddenly the quiet is interrupted by a scratching sound on the outside of my shelter, like fingernails. Immediately I think, Police—they found me. Didn’t that man in the truck say people are looking for me?

A police officer would probably take me back. But back where? I can’t go back to nothing. I brace myself and prepare for an intruder. But the sound has stopped and all is still and quiet again. Did I imagine it, like everything else?

What would I tell a cop? I’m supposed to start my senior year. These are supposed to be the best years of my life, but I know they are not. The only things I remember clearly are from long ago, like where I was born, the sound of gulls in the morning, and the smell of the ocean coming through the window. I remember being a little girl. I remember painting a mural of trees on my bedroom wall. I remember my mother and father. They want what’s best for me, but how do they know what is best for me when I don’t have a clue?

And then I remember Jake. He gave me a bracelet. I look at my wrist. I am still wearing it—it’s an embroidery rope of all different colors. I run my finger along the silklike braid. Jake was real. Jake mean

t something.

But how did I get from there to here? I’m not anywhere near the ocean—there are forests and fields all around; nothing is familiar.

There is the scritching sound again, followed by a whimper. It’s some kind of animal—could be a raccoon or a skunk. I’ve heard raccoons can be vicious, and I don’t relish the idea of skunk spray, so I stay very still.

Then, thumping on the side of the box and a shiny black nose pokes through the opening. The nose belongs to a dog. A damp, dirty, smelly dog.

“Shoo,” I say. It doesn’t come any closer, but its tail goes wild, whomp, whomp, whomping against the heavy cardboard. “Go on, get out of here.” I try to wave it away.

But the dog doesn’t listen. It noses in the rest of the way and sniffs. It has dark-gray mottled fur and flecks of white on its long, skinny tail. Its ears are alarmingly tall and point straight up. Its whole body wags like crazy. He is small enough to fit in the box with me but too big to be a lap dog.

I can tell by the way he lifts his head toward me that he wants me to touch him. His fur is matted and he needs a bath. I am afraid he might have fleas and who knows what else. I hold my hands away.

“Don’t come any closer,” I say.

He keeps sniffing around like he’s looking for something. His eyes rest on the Styrofoam container I’d tossed in the corner. Of course, he’s attracted to the smell of the rotten, leftover spaghetti.

“Is this what you want?” I hand him the box. “Go ahead, I’m not eating this crap.” As I say it my stomach growls. The dog hesitates a second, then takes the container in his mouth and slowly backs out the way he nosed in.

BEFORE

I thought romance would never happen to me, that somehow I had whatever it was that made me totally unnoticeable to anyone. I had pretty much given up on the idea of love. But then something happened.

It was a white-hot afternoon—unheard of, even for July. There was nothing to do, so I figured I’d buy an ice cream cone and go to the town beach. I made it halfway down the driveway before turning into a torrent of sweat. I had to lie down on the grass and close my eyes. The sun seared through my lids. The music pulsed through my headphones.

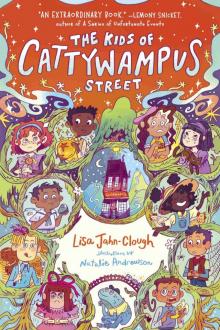

The Kids of Cattywampus Street

The Kids of Cattywampus Street Nothing But Blue

Nothing But Blue